Weight problems and obesity result from the combination of many factors, including physical, social and psychological aspects. Here we look at some factors which can be classified as environmental, although they may interact with psychological processes. The term “obesogenic environment” refers to “an environment that promotes gaining weight and one that is not conducive to weight loss” within the home, community or workplace. In other words, the obesogenic environment refers to an environment that helps, or contributes to, obesity. Some environmental factors promoting obesity are:

Each of us lives in our own unique environment, so the obstacles and advantages for achieving and maintaining healthy habits are also unique. Let's do an exercise. Think about something/someone in your life that is "weighing" on you. In what ways does this thing/person promote weight gain and obesity? Be honest with yourself. If you can't see the problem you won't be able to fix it. By taking an honest inventory of the environments you live in, you are in a position to make changes that will pay off in better health and wellness. The beautiful thing about this type of self-development work is that it doesn't feel like work, because you are making your life both easier and more productive at the same time. Stephen Stotland, Ph.D.  Mindfulness has become a popular topic in relation to weight control. Many are suggesting that learning to eat more mindfully should lead to healthier eating, and possibly to better weight control. That has not been proven yet, although it does seem like a logical prediction. So, what is mindfulness, how do you get more of it, and how does it improve weight control? Mindfulness refers to a state of mind in which we notice what we are thinking and feeling, without getting lost in our thoughts or trapped in our feelings. Mindfulness training is thought to gradually develop the quality of “equanimity”, which means that we get better at not amplifying our reactions, be they positive (“the ice cream is so good, I can’t stop eating it”) or negative (“I can’t take this feeling and I must make it go away this instant”). In meditation practice, we try to notice everything non-judgmentally, without acting on it. Engaging regularly in some form of mental practice, such as mindfulness meditation seems to have beneficial effects on the quality of our mindset. To get the most out of our efforts in pursuit of our goals, such as to get in better shape or to increase our overall life satisfaction, it helps to deal with the behaviour change process in a mindful manner, focusing more on the day-to-day process and less on the outcome. When it comes to weight control, the concept of mindfulness has many implications and applications:

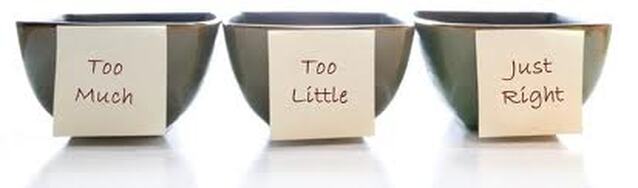

Is mindfulness enough? When we think about the decision-making process for eating (or exercise), we realize that being mindful about our impulses to eat or not eat may not be enough to produce better choices, although it is a necessary first step. We also need a strategy such as the one I define as "moderation". The question then is how do mindfulness and moderation relate to each other? Moderation starts with the intention to eat the "right way"; i.e., the optimal amount and types of food. What is "right" or "optimal" is hard to define, so we can think of it more as a general strategy, like a meta goal. There is no specific requirement to follow a particular diet or eating plan, but more like a strategy to eat "reasonably and intelligently." I sometimes refer to moderation as "intelligent restraint." There are as many variations on what this looks like as there are individuals, because we have our own individual preferences and biological needs for food. The strategy must map on to what we need to support our health and wellness. Intelligent Restraint is different than the prototypical "diet mentality." The typical diet mentality is a type of "rigid" restraint, based on strict eating rules ("eat this, not that"), anxiety about breaking the rules, and guilt and loss of confidence if and when there's any lapse in the restraint. In contrast, intelligent restraint is being a smart and reasonable eater. It does not mean being inflexible. For example, taking a small ice cream cone instead of a medium or large one, realizing that the first 10 bites are the best, after which the satisfaction per bite decreases rapidly, and remembering that there will be other occasions to eat ice cream, and this is not the last chance. This mindset, to the extent that we follow it, leads to a significant reduction in unhealthy eating and an increase in healthy choices, while satisfying our taste preferences at the same time. Thus, the most advanced weight management mindset, and the one that we want to cultivate, is best referred to as "mindful and moderate". The operation of this mindset works on the principles of sensitivity to internal signals, along with an attitude of moderation. To summarize, you need to learn to pay attention to your body's signals and you also need to sharpen your intelligent restraint. Mindfulness is necessary, but so is good judgment. In our program, we work to help you move from rigid restraint to intelligent restraint, and ultimately to mindful and moderate eating. These principles apply to the way you eat, and how you regulate your physical activity, stress management, and general health and wellness. In other words, it's kind of an all-purpose strategy, perhaps even a way of life. Stephen Stotland, Ph.D.  Setting goals and working towards them is the most basic formula for behaviour change. Think about a simple goal, say "take a walk, each day". In the way we have stated this goal, there is no rule for how long to walk for, when, where or with whom. It's simply, walk each day. Over time you will be able to judge if there's an improvement in your daily walking. You will not need to quantify it, or provide a percentage improvement, but you should have a clear sense of whether you've made a small, medium or large improvement in your walking since the last benchmark. If you have a strong sense of walking better/more, that will likely be accompanied by some improvement in your overall self-rating of fitness, and other changes that you can notice. Let's branch out a bit and think about a second goal, to "eat some veggies", each day. This is another seemingly simple task. Think about it some more however and you will realize how much room for improvement there is in your eating of veggies. This is not an endorsement of veganism, since eating veggies is important no matter what else is included or not included in the diet. Again, think about a gradual improvement in your veggie eating, and how much better that would make you feel in general. After focusing on these goals for a while, you might add other simple goals, such as "do something to relax". Or add other eating and physical activity goals. Gradually you will gain a new set of healthy habits. All of that probably adds up to some big changes in your health and wellness, especially over longer periods of time. Think small, and remember that a journey of 1000 miles begins with a single step. That is a cliché, but it is undoubtedly true! Stephen Stotland, Ph.D.  My previous blog post discussed the basic ideas around "readiness". Hopefully, that inspired some people to think about what it means for them, and perhaps they took our Weight Management Readiness Test to give themselves a baseline measurement. In this post I will explore the concept of readiness more deeply, to explain how we can use it to accelerate the process of behaviour change. SPOILER ALERT: if you have not yet taken the test, this would be a good time to do so. Then come back and read on. ________________________________________ To communicate to people about Readiness, it was helpful to find a way to summarize all of the various factors into a single readiness score. The score gives us an overall sense of our current strengths vs. our weaknesses in regards to achieving our weight management goals. However, in summarizing this way we lose some of the more specific information that explains the differences between two people who may have arrived at the same score in different ways. As it is currently organized, the readiness score ranges from -4 to +4. A score of -4 means that perceived obstacles to change are at a maximum, while confidence in change is at a minimum. Conversely, a score of +4 implies the reverse scenario, with maximum confidence and minimum obstacles. Those situations are perfectly clear. For the -4 person, the task seems quite hopeless at present, while the +4 person sees it as smooth sailing. The further we move away from the extremes the more ways there are to achieve the same score. For example, a score of 0 means that the individual judges perceived obstacles to be equal to their confidence in overcoming those obstacles. But that same result can occur at all points on the scale: 0 obstacles & 0 confidence, max obstacles & max confidence, or moderate obstacles combined with moderate confidence, all produce a score of zero. It is not clear that these different scenarios are really equal. The readiness test can be used in two ways, and one is probably more valid and useful than the other. First, we can use the scores to compare people, to judge how ready one person is compared to the average person. The second use of the test is to explore an individual's various ideas about weight management, and to see how those ideas change over time. While both strategies have their place, it is the second that is most useful in a coaching context and can help us get started in the process. Let's look deeper. We'll start with the first question on the test. It asks how much you agree with the statement, "It's very important for me to lose weight, but I'm having trouble making it a top priority", on a 5 point scale from disagree completely to agree completely. What is this question getting at? What does it mean to make weight loss a "top priority"? Does it have to be the top priority, or can it just be a high priority? Most people answering the test respond with agree completely or somewhat with this statement. This implies that they feel they will need to put most of their focus on this task. Exactly what they will need to do is not specified. Is it to get on the scale each morning? Is it to take more time in deciding what to eat? Is it taking a walk each day? When we say that achieving a goal requires it to be a top priority, it seems we are saying that it will take a lot of effort, that it will take time and energy away from other activities, and that we will have to sacrifice to achieve this goal. As you can see, there can be a lot packed into the response to this one question. The more we perceive the task as heavy, demanding, costly, effortful, the bigger a mountain we see ahead of us, the less likely we are to get started. Becoming more psychologically ready means deconstructing what it means to prioritize the goal, finding smaller tasks to focus on, to reduce the emotional burden of commitment. Now let's look at the companion question from the second half of the test. This one asks how confident you feel that you can "Make weight control a top priority", on a 5 point scale from not at all confident to completely confident. What we typically find is that the same person who agreed somewhat or completely that they have trouble making weight management a top priority, now says that the are quite confident or completely confident that they can do so. They're saying it's been hard to prioritize weight control but they are confident they can. Where is the newfound confidence coming from? Is it because they feel something has changed in their circumstances? The time is somehow right? Their mind is more made up? The stakes have changed and the goal is even more important now than it was before? They plan to join a program which they think will provide them the support and direction that will change things? In wondering how these two apparently opposing thoughts can exist at the same time I am not doubting that the person really feels this way. What I think is important is to explore a little deeper beyond the multiple choice responses, to understand why the person thinks this time is the right time? As we go through the rest of the questions, we get some ideas about what the specific challenges are for each individual. For some it is related to the place of food in their life, for others it's learning to incorporate exercise, and for many it is how to organize this process and how they can persist over the long-term. When we look closely at the responses to each question, we get a picture of the individual's current set of beliefs about weight control. Our goal, like our clients, is to find a formula that works and that does not feel like a huge burden. As their program progresses, clients become more and more "ready," not to begin the journey, but to keep taking steps each day, until it is no longer a question of change, but simply continuing what has become natural, automatic and intrinsically rewarding. It is this that we wish for all of our clients, and all those who embark on their own journey of self-development. Stephen Stotland, Ph.D. When we begin any new project, it makes sense to ask ourselves if we're ready? Before leaving on a road trip, we check that the car is in good working condition, that the tires have air and the tank is full, that we have clothes, money, and an interesting itinerary. This is a simple, obvious example. Sure, there are dramatic and entertaining examples of people who launched themselves into great adventures without thinking or planning and somehow succeeded, but that's probably not how we want to model ourselves.

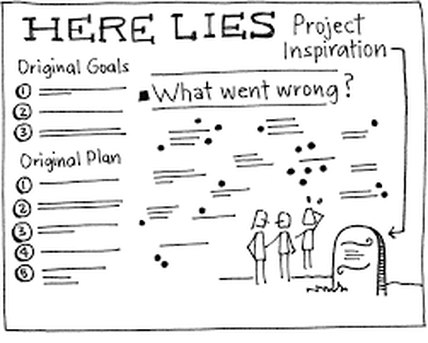

When the change we're talking about is a change in ourself, we should take the time needed to consider the implications and the commitment that will be required. First, why do we want to change? If those reasons are so clear to us now, why hasn't it already happened; what has been keeping us in our old pattern? Second, if we make the change, what consequences will that have? How will it affect other things and other people in our life? There is a maxim (from Benjamin Franklin) that "failure to prepare, is preparing to fail," and in the case of personal, behaviour change, a good part of the preparation is getting clear on the Why, before we get into the How. An important insight from psychology in the last 40 years is that change occurs over a series of stages. Changing habits is overcoming the "law of inertia" (Newton's first law), which states "if a body is at rest or moving at a constant speed in a straight line, it will remain at rest or keep moving in a straight line at constant speed unless it is acted upon by a force". What is the "force" that gets us to change our habits? A smoker who is not thinking about quitting is in a stage called "pre-contemplation". If we were to see into their thoughts we would find that the Pros of smoking (it's relaxing, fun, cool...) are a lot greater than the Cons (unhealthy, expensive, smelly...). To get this person to begin thinking about quitting (which we call the stage of "contemplation") something has to change the balance of Pros and Cons in their thoughts. As the balance tips towards the Cons being greater than the Pros, the person is closer to a change. But that's not enough to make change happen. In addition to strong reasons to change, we need the belief that the change is not only possible, but within our capacity to make it happen now. Let's unpack that a bit, and use a relevant example to make it more real. Are you able to change your eating and exercise habits enough to lose 10 pounds? Are you able to maintain those changes to ensure that the 10 pounds stays off for the next 5 years? If you answered differently to the two questions, then you may believe that short-term behaviour changes are easier than long-term changes. Perhaps you think that over time other factors may counteract your efforts (maybe you think your metabolism will slow down in response to the weight loss)... There is a complicated matrix of thoughts and beliefs in our minds, some conscious and others less so, that determines our motivational state. That's why asking a simple question like "do you believe you can lose weight and keep it off?" is not very informative. To really understand how psychologically ready you are to accomplish this goal, or any other behaviour change goal, we need to dig deeper. In order to help explore this I created a questionnaire called the Weight Management Readiness Scale, that presents the kinds of thoughts that seem both common and central to this process. This is based on my decades of working with people at all stages of this journey. Please give it a try, but as you do so, be honest with yourself about what you actually believe, not what you think you should say to get the best "score" or what you wish you were feeling. o0xl0mhj.paperform.coClick here for the Weight Management Readiness Scale Best wishes for a safe and successful journey! Stephen Stotland, Ph.D.  You need to stop sometimes. Coming back to the present moment is a gift to yourself. You may be the most productive and creative person, with a head filled with new ideas, important tasks to complete, people to talk to, etc. Or you may be someone with a lot on your mind that you wish wasn’t there, worries, regrets, resentments, that you can’t seem let go of. You may spend a lot of time thinking about your next meal, what you should or shouldn’t eat, what you would like to eat, your mouth watering in anticipation. You may be excitedly thinking about your exercise routine and the great progress you’re hoping to make and next challenge you want to accomplish and can hardly wait to do more. Or you may be thinking about the dinner party you’re arranging or invited to attend, and what to wear, what to bring, and how much you want to go, or not go… Your mind is filled to overflowing with all the good and bad things you’re engaged with, and it’s difficult to put them aside, even for a brief moment. It seems the only time you rest is when you’re asleep, and even that is not so restful. What is going on? Where’s the fire? What’s the emergency? As you proceed on your weight and wellness journey, you are of course working actively to improve your ways of eating and moving your body, which takes planning and practice, so good for you for sticking to it. But you also need to learn to rest sometimes. To release the burden. Put down your baggage. Find peace in the moment. Be kind to yourself. Imagine you’re in charge of the process for someone else, perhaps a close relative or friend. You help them devise their plan of action, you monitor their progress and celebrate with them as they move closer and closer to their goals. Will you be a harsh task-master? Will you criticize them if they skip a workout, or indulge in a small piece of cake from time to time? Will you push them to do more, even when they’re exhausted? Probably not, at least we hope not! More likely, you will act like a responsible parent, who loves her child unconditionally but knows what’s best for them. You will instruct, model, encourage, push, explain, persist, give constructive feedback but also lots of hugs, and make sure he or she gets their rest. Almost everything will work again if you unplug it for a few minutes… even you. Alice Lamott Talking about weight control, or talking about life, we need to find the balance between “go, go, go/onward and upwards,” and “stop and take a break.” Is there a danger that resting turns into backsliding and complacency? Not if the rest periods are effective, meaning that they provide the rest, relaxation, recuperation and letting go that brings wellness and restores the motivation to get back to the action. Stephen Stotland, Ph.D.  Many people lose weight but remain “fragile” in the sense of being at risk for regaining the weight. This article explores the reasons for this fragility, and ways to help you prevent relapse. A glass is a great example of a stable but fragile structure. A glass may survive for a long time if you handle it with care and avoid dropping it, but it’s always a moment away from destruction. Time does not make the glass any less fragile. Let’s explore why some dieters seem to be as fragile as the glass, and the potential solution. A central issue in weight control, as it is with every other type of behavioural problem, is how to reduce the risk of relapse. In fact, it’s not an exaggeration to say that reducing the risk of relapse is the primary task of treatment. Many methods can initiate change, such as a week at a health spa (fun!) or a 21-day diet and exercise plan (not fun!), but these short-term interventions do not fix the long-term problem. Of course, the initial focus of all treatment is symptom reduction (losing the weight, stopping drinking, recovering from depression, etc.); this is the necessary first step. You must lose the weight before you can confront the challenge of maintenance. However, you need to start preparing for maintenance before you get there and not take it for granted. Thus, we often see people launch themselves into an intensive program – the more stringent the better – and get dramatic results. They feel happy, proud, and confident, but unfortunately, they go off course at some point, feel defeated and discouraged, lose focus, and find it difficult to get back on track. No matter how well it seems to go during the initial intensive, “boot camp” phase, these individuals remain “fragile” with respect to their risk of relapse. The reason for the dieter’s fragility is two-fold: First, the intensive regime is not physically or psychologically sustainable and does not represent a real lifestyle change. Real lifestyle changes are built from less dramatic small shifts in daily life that add up to big changes over time. Real lifestyle change requires you to deal with all the stresses and strains and competing demands of “your” life. Second, diets do not teach people how to master the relapse crisis itself. This is another key challenge in long-term behaviour change, and where psychology plays a very important role. It’s learning to deal with, and indeed to learn from, the relapse crisis that is the key to lasting change and successful weight loss maintenance. The most well-established model of relapse and relapse prevention was proposed about 40 years ago by a psychologist named Alan Marlatt. His initial work was with alcoholics, but the model has since been applied to all sorts of behaviour change. In the relapse prevention model, the first question is how one copes with a “high risk” situation. High risk situations are those that increase the likelihood of an initial “lapse” (a slip back to the old behaviour) for an individual; these high-risk situations often involve negative emotions and interpersonal situations, but may also involve positive events such as parties, holidays, and celebrations. When we face such a situation we are challenged to find a way to cope. If we manage to cope successfully, we gain knowledge and confidence, and reduce our future risk of relapse. On the other hand, if we fail to cope, giving in to temptation and deviating from our plans, we may lose confidence and become even more prone to relapse. Importantly, even a failure to cope can lead to learning, as we come up with strategies to avoid or cope with similar situations in the future. Thus, it is not just the occurrence of a lapse that is important, but how it is interpreted. If a lapse is interpreted negatively (“I knew this would happen, changing my bad habits is impossible!”), it can lead to a spiral of bad behaviour and loss of motivation (“what the hell, I’ve blown it, so I may as well continue….at least I’ll have the pleasure of eating”). If one’s confidence is shaken beyond a certain point of no return, we are likely to conclude that further efforts are pointless and quit. It is as if each time we face a high-risk situation we meet a fork in the road, offering the choice between learning or quitting. We need to develop what’s called a “growth mindset,” which is thinking that we can learn through trial and error, and practice. Most of the patients we see tell the story of having lost and regained weight many times. One of the first questions we explore is what were the causes of the weight regain? If we can pinpoint the causes of past failure we can turn them to our advantage. For example, one lady described having lost 50 pounds with a combination of better eating and regular exercise; nothing unusual or extreme in her approach and it was going great…. until she fell back into her usual pattern of caring for everyone else and not making time for herself. Thus, she reverted to her old habits of not planning or organizing her eating and not exercising, and inevitably regained the weight. In embarking on another attempt to fix her weight problem, she needed to be very clear from the start about what it will take to avoid a repetition of what happened. She will need to truly address her lifestyle issue of not making herself a priority in her own life. In the world of business, leaders are advised to get their teams to do a “pre-mortem” before launching into a new program. The idea is to imagine that the program has failed and to think of all the reasons why it did. This is to provide insight into all the pitfalls that should be avoided. The reason this exercise is a good idea is because of the natural tendency for people to be overly optimistic when in a highly motivated state, and to ignore potential risks. We really want to achieve the outcome, so we convince ourselves that we are bound to succeed. That’s a dangerous attitude, and one which makes us more “fragile.” Better to start by facing the risks that lie ahead and using our past experiences to teach us. That is the key to relapse prevention! Stephen Stotland, Ph.D.  It’s obvious that you don’t have to be “hungry” to eat. We eat for all sorts of reasons, such as the time of day, the availability of food, seeing other people eating, as a distraction, reward, coping mechanism, or “just because” we feel like it. Let’s define hunger as a state in which we experience physical sensations resulting from a lack of food energy. We may or may not initially pay attention to those sensations, or label them as signs of hunger. As the sensations intensify, we are likely to become increasingly conscious of the empty feeling and rumblings in the stomach, perhaps a feeling of fatigue, and a growing need to eat. Eventually, we may become irritable and have a hard time concentrating on work or other matters. We might think of a Hunger Scale with ‘extreme hunger’ on one end and its opposite – ‘extreme fullness’ – on the other end. Let’s define extreme hunger as 0 and extreme fullness as 10. Those states are easy to imagine, but what about all the steps in between? What does a 2 feel like? Or a 4? Where does fullness begin? At what point does fullness shift into overeating? Is the middle ground between hunger and fullness a “neutral” state? When you say you are “hungry” an hour after supper, what sensations are you actually experiencing? Thinking about the hunger – fullness continuum we realize that these are complex concepts. Neither hunger nor fullness are straightforward, or easy to define. They are partly physical and partly psychological, depending on attention, interpretation, and situation. The implication is that there is only a loose association between these internal states and our eating behaviour. Sometimes we eat because we’re hungry and stop because we’re full, but not always. The psychologists Peter Herman and Janet Polivy discussed this some time ago in what they called their “Boundary Model” of eating. In their model, individuals have well-defined hunger and fullness boundaries, which are the points on the continuum beyond which the person feels strong physical feedback indicating hunger or fullness. This feedback is in some sense painful or unpleasant, and it motivates us to eat, or stop eating. What is interesting is that each person’s boundaries may differ, so that given an equivalent physical state (degree of energy depletion) one person would describe it as a 4 (little or no hunger) and another as a 2 (strong hunger). The same is true, they suggested, for the fullness boundary, so that the same amount of food may produce a 6 (little or no satiety) for one person and an 8 (very full) for another. These differences may be due to learned perceptions, or inborn sensitivities. An open question is what is the effect of eating less, does it eventually cause our stomach to “shrink?” The stomach is a small organ (about the size of a fist) but can stretch to accommodate large amounts of food. In fact, the stomach is always stretching and shrinking as we eat and digest food, allowing the stomach to empty, but it is true that if we stop overeating the stomach is, by definition, less often in a highly stretched state. More importantly, if we start eating less we may eventually adapt to the sensations produced by the smaller meal and come to define that as fullness. It is not so much that the stomach has shrunk, but our expectations that have been retrained. That is the kind of learning that we hope for, and that will make healthy eating choices “easy,” and not forever a matter of restraining oneself. What about the part of the continuum between strong hunger and fullness, say the 4, 5 and 6 on the scale. Herman and Polivy called this the physiological “zone of indifference” (ZOD) meaning that the body’s homeostatic systems, those responsible for motivating us to eat or stop eating, are indifferent to whether we eat or not when in this neutral zone. We receive no strong feedback signals, and so we are “free” to choose to eat “if we feel like it.” Thus, in the ZOD, we are especially prone to eating in response to emotional, social, and food cues. It is interesting that people usually say that they eat because they feel hungry, in effect mis-labeling the real reasons, because we have been taught that the only good reason to eat is because we are hungry. A good step is to be honest with oneself about one’s motives and admit that one eats for other reasons than hunger. Several writers and clinicians tell people that the way to eat better and be healthy is to listen to signals of hunger and fullness and base their decisions on trying to satisfy their physical needs. While this is a nice idea, there is no evidence that it works as a method of weight control. As we have discussed, hunger and fullness are complex and confusing signals. In our view, using hunger and fullness signals to guide eating decisions is an “advanced” strategy, one that we introduce to our patients months into the treatment process. For the vast majority of obese individuals, preliminary work based on creating reasonable eating routines and structures is necessary to get the process started. Once the individual has learned to do that, and has gained confidence and flexibility in weight management, we can begin to shift to a more internal awareness-based type of self-control. If you’ve read our earlier blog post on the stages of weight control, you know that this shift from external to internal control strategies takes place in stages 5 and 6. It’s important to keep reminding ourselves that you need to walk before you can run, and to run one kilometer before attempting a 10K – in other words, you need to be a novice, before you become an intermediate, or a master. Keep working at it! Stephen Stotland, Ph.D.  Let’s go a little deeper. Step back from the edge and look out, up, and down. See the empty spaces. Realize it’s almost all there is. And you’ve been trying to fill up the emptiness. Not even wanting to acknowledge that it’s there. So, you keep talking, joking, buying stuff, eating, and drinking. Don’t stop, never stop. Crashing into sleep, but not resting even then because you wake every minute or two. Gasping for breath. Not able to fill the lungs and needing a machine to help. No rest for the weary. Would you like to stop now? Embrace the emptiness. See the beauty that lies within. The lake smooth as glass. The forest so quiet without even a breeze to rustle the leaves. The sleeping baby untroubled by worry. What is better than a moment of peace? If you stop you won’t disappear. You can rest for a while and then get back to the action. Enough is enough. You are more than enough. Stephen Stotland, Ph.D.  Tears run down his cheeks as he asks me why he seems to be set on a slow suicide. Why, he asks, would he go down this self-destructive path when he has so much to live for? He’s talking about how he let himself get so obese, why he let it go so far. I hear him and see the smart and jovial man in front of me, and I’m not sure if his theory is correct. In effect, his behaviour is indeed a slow suicide, since as the years go by and the weight keeps increasing, he becomes less and less healthy, with diabetes, hypertension, sleep apnea, and joint problems, but does he really have the intention or wish to die? Is he really on a mission of self-destruction, or is there a better explanation? This forces us to consider some deep questions, such as “is chronic overeating and the severe obesity that it produces a voluntary act, or due to an addiction completely outside the individual’s control?” I have a couple of tests for this: first, imagine you have a choice between overeating and saving the life of someone you love…which do you choose; second, less dramatically, imagine you have a choice between 10 million dollars and overeating, which do you choose? The answers are obvious, but you might still doubt that the person will stick to the commitment. “Slow suicide” is a harsh judgment, but one I’ve heard before. A slightly less extreme version is “am I self-destructive? Why do I sabotage myself?” Psychologists have defined three types of self-destructive behaviour: 1. The person foresees and desires to harm himself, 2. The harm is foreseen but not desired, and 3. The harm is neither foreseen nor desired. Research suggests that the second type is most common, and the first type is rare except among individuals with severe emotional disorders. The common form of self-destructive behaviour among normal individuals is due to disregarding costs in favour of immediate pleasure or relief; this means to favour short-term benefits (e.g. the momentary pleasure of eating) despite long-term risks, and this is especially likely during negative mood states. Thus, unhealthy behaviour can result from impulsive choices based on the desire for immediate gratification, or what behavioural economists call “delay discounting” (delayed outcomes are perceived as less valuable than immediate ones). Unhealthy behaviour can also be the result of routinized, automatic behaviour (“bad habits”) – see the food, want the food, eat the food… We are all creatures of habit, and it takes effort, or at least “intention plus attention” to override those habits. A useful analogy for the dilemma one faces in trying to change an unhealthy behaviour pattern is the following: a boat is cruising along in the ocean and the crew suddenly realizes it is heading for an iceberg (for want of a more likely obstacle!). The captain orders the boat to begin turning and the necessary actions are taken to produce this effect. Slowly the boat begins to turn, first slowing its momentum in the original direction and then gradually changing course. The boat in motion can not stop on a dime and jump course; it’s a gradual process, with the time needed to make the change proportional to the momentum that must be overcome. So too, a person with a long history of bad habits will need time to reverse course. Hopefully, the corrective actions were begun in time! My patient and I have been meeting weekly for a couple of months, and we have a good rapport. He’s talked about many things, while losing about 40 pounds so far. We still don’t have “the” answer to his question. I resist the impulse to tell him his theory of “slow suicide” is incorrect and leave the question out there. Perhaps it will help him dig deeper and motivate him to find the will to live. We have a long way to go, both in terms of his weight, and to arrive at a satisfying explanation for how he got so big and, perhaps more important, why he won’t go back. In developing our theory, my patient and I work as collaborators with a shared mission. In this case, because he comes from the business world, we say that he is the CEO (of the weight management company) and I am the executive VP of strategy. We work together to set up goals and plans, and monitor implementation and results. We are working to create momentum in the right direction, and we seem to be moving that way. Now we must stay the course… Stephen Stotland, Ph.D.  It has been almost a year since my last blog post, and I'm almost reluctant to write this one. You see, so much has been written about weight control and healthy habits, perhaps it has all been said before. I don't want to waste my time (or yours, good reader) with another exposition on "how to set SMART goals" or "how to stick to your New Year's resolutions." Know what I mean? Personally, I've read enough of those....yup, I still get sucked into reading them sometimes, because of the catchy titles no doubt ("7 steps to total freedom and happiness....and p.s. you can make a million doing so!!!"). In counseling people (patients, clients, fellow human beings) on how to achieve their goals, the problem is rarely a lack of knowledge, and when it is that is easily fixed with a visit to Mr. Google. The real issues lie at deeper levels. My job is to help my patient settle down, look at him/herself, pick a direction to move toward, and keep going when times get tough. There's no secret formula, but the process is always exciting, creative, and it's always my privilege to witness. Does it always happen? Do all of my patients achieve their goals? Yes, and no. Sometimes the journey never gets started, as there is no "click" between he or she and me. I have the experience to know that I can't get through to everyone. But all who show a real willingness and desire to change get somewhere. Those who are seeking transformation without any effort will have to look elsewhere.....Hey, I'm sure there's an article (or 10, or 1000) that has the "7 steps to effortless change." All the best for 2018! Stephen Stotland, Ph.D.  Time is on my side, yes it is. Time is on my side, yes it is. - Rolling Stones, 1964 Time is a key element in the process of self-change. It takes time to do the things we need to do to achieve our goals. This requires organization and prioritizing, to "make" the time that it takes. It also takes time for the changes to manifest. We can do all the right things, and still have to wait to see the positive results. Sometimes, in fact, it seems that nothing is happening, and we have to search inside for the patience, to give it more time. It is true that time is a limited resource. It's something we can't buy more of. As we get older it seems that time speeds up, as we sense that we have less and less of it. The moments become more precious when we understand that we can't get them back. Time spent with family and friends is not to be wasted. These insights are by no means easy to assimilate. They point out the essential things in life, and remind us to pay attention, to take it in. At the same time, there is the anticipation of endings and loss. All good things must come to an end. This too shall pass. Everything is impermanent. These are some of the hard truths of life. But it is how we deal with the existential dilemma that matters. Do we collapse into depression because nothing lasts so nothing matters, or do we seize the day, and savour each and every drop of it? These philosophical questions have everything to do with the pursuit of better weight control, even if you're unlikely to confront them in any popular diet book. In choosing to take on the challenge of weight control, one is accepting that 1. it will take time to get there, 2. it will take time to stay there, 3. there's no telling how long you will get to enjoy the fruits. Furthermore, weight control has everything to do with how you deal with the moments, as well as the days, weeks, months and years. In the moment, there is often an urgency, a need to satisfy a desire, an emptiness, a hunger, or some other impulse, that pushes you to act NOW. You need to pull back, give yourself time, to think, and to choose to stay the course. Being in the moment, you can pay full attention to preparing the food you like, only as much as you need, eating it slowly, savouring each bite, and taking a moment to reflect, so that you remember, that it was good, and satisfying, and will be enough to last until the next time.... Time is on your side, if you allow it to be. Lastly, remember that the next 5 years will pass, whether you're paying attention or not. Better to be there, and make the most of it. Think how happy you'll be in 5 years, looking back on all the intelligent efforts you've made and all that you've accomplished, and enjoyed. Stephen Stotland, Ph.D.  I just got back from several days in the mountains, and I came home with a few insights. Here's what I learned: 1. when you explore the mountains, you need a plan (a destination and a path to get there) and you need to stay mindful of the signs, to make sure you stay on the path 2. when you have a long journey, you need to keep moving, except for short rests 3. sometimes you go slowly, sometimes fast and bold, but it's important to move steadily, and safely 4. one step at a time 5. look around...nature is BIG 6. listen to experienced guides 7. choose your companions wisely, and respect each other 8. carry your own load; your companions have their own stuff to carry 9. help others when they need it 10. a false turn can take you far off course - stick to the path 11. try to leave things the way you found them 12. be adaptable to changing circumstances 13. dress appropriately 14. if you can't sleep, rest 15. eat well - for nourishment, energy, and enjoyment; share your food 16. you can do a lot more than you imagined 17. there is a lot to learn 18. keep the fire burning at a comfortable heat; occasionally let it burn out so you can clean up the ashes 19. working really hard leaves you with a satisfying kind of relaxation 20. the sore muscles are a good kind of pain. I know that these insights need regular updating. The benefits and lessons of nature need to be repeated. Stephen Stotland, Ph.D.  I started studying obesity and behaviour change as a grad student, which is now more years ago than I wish to admit. My perspective was, and is, that improving weight control is a kind of learning, so the same principles that explain how we learn anything or develop any new skill must also apply here. If we think of other types of personal projects, such as taking up a musical instrument or learning a new language, these too are difficult tasks, and not everyone who starts goes on to achieve a high level of mastery. What is it that separates those who quit from those who go on to become highly skilled experts? I think about weight control in the same way. I've been at this for long enough and witnessed enough people trying, some failing and others succeeding spectacularly, to understand that weight control is complex. I prefer to think of each case as a unique "weight control story." What do I mean by "weight control story?" When I meet a new patient I want to understand what they think about their problem. How important is it? Are they coming on their own volition, or mostly to satisfy someone else (a loved one; a doctor)? Given that the problem has been there for years, why is now the right time to fix it? What changes have happened to create this motivation? Why are they seeking help, and why the specific kind of help that we offer in our clinic? What do they hope to accomplish? What do they hope will happen in the next month, 6 months, 1 year, 2 years....? What are they afraid of? What obstacles do they anticipate? Of course, the story doesn't start there, and there are roots of the problem that we need to look at. Does it go back to childhood and family traditions? Are there recent or current life situations that are contributing to the weight problem? Do they think that better weight control will solve other problems, or perhaps set the stage for solving them? While people want to lose weight to improve their health and prevent future health problems, there is usually more to it than that. Weight control is seen as a key ingredient in improving one's life, a prerequisite for getting back to favorite pastimes that have been abandoned, improving self-confidence, getting organized, getting into the dating game... in some way or another starting a new chapter in one's life. So it's a story that we jump into midway. Imagine opening a book in the middle and reading a few pages. You might have some idea what it's about, but surely you'll want to go back to the beginning to fill in the gaps and figure out how it got there, and you might be tempted to jump ahead to find out how the story ends. But my patients are not books that have already been written...that's what makes them so fascinating. There is no jumping ahead to the last page, and even the looking back to understand the history is only a reconstruction. Primarily we are here in the present, trying to get focused, keep it together and move forward. Sometimes I feel like the conductor of the train, sometimes like the co-pilot, sometimes a teacher, sometimes a confidant, sometimes an interested observer, always like a cheerleader. I want to say, "let's go, you'll get there, we'll get there together." When my patient and I are on the same page and trusting the process it sometimes feels like magic. I really like my work. When I feel that I've grasped the patient's story and helped them make decisions about what they want to do, or when I feel I've helped them come to terms with difficult emotions that they haven't been able to understand, and when I can offer a new strategy for coping with stress or improving habits, I feel very satisfied. When I do my part it's up to the patient to do theirs....it really takes two to tango! Obesity is a big problem for my patients, and for society. We really do not have a consensus about what to do about this. I don't think the answer is taxing soft drinks, or campaigns to encourage people to eat vegetables and walk more, although those kinds of efforts can't hurt. I will continue working with people to create real change, and exciting stories! Stephen Stotland, Ph.D.  How many articles have you read that began with some variation on the proposition: “weight control is confusing, and this article will clear up the confusion for you,” and yet the result is just more confusion. So, if I were to say that this article aims to “once and for all” clear up the confusion, I would hope that your completely rational response would be to stop reading immediately. Therefore, I shall make no promises of that sort! We all know one thing and that is that weight control is hard, even if we may disagree about what makes it so. Let’s quickly run through some of the most important reasons: 1. The environment is a minefield of temptations, both healthy and unhealthy, and often we are faced with too many choices and an overabundance of food (yes, there are still too many hungry people on the planet, but that is a different problem). 2. Social relations often revolve around food, especially holidays, celebrations, romance, watching sports, playing sports (“beer hockey, anyone?”) ….and I could go on. 3. Too many cars and not enough walking. 4. Obesity is in some sense a self-perpetuating condition, with metabolic, psychological, and social adjustments that tend to promote continued weight gain. 5. The very idea that weight control should be easy, which brings us back to the influence of the media and the weight loss industry, always ready to sell us the latest “answer,” which only encourages wishful thinking and short-lived efforts to lose weight. Once we accept the evidence that weight loss is hard, is the intelligent choice to give up and go with the flow? It is possible after all that the pharmaceutical industry will come up with a pill allowing us to overeat, remain sedentary, but stay thin and perfectly healthy…. just when is that pill scheduled for release? No, I think the answer inevitably comes back to the time-tested method summed up in classic quotes such as “slow and steady wins the race,” and “a journey of 1000 miles begins with a single step,” or even “moderation in all things, even moderation.” The point is to envision a desired future and start moving in that direction, and to keep moving even if at times progress is slow, backsliding can happen, and the results are less than anticipated…. keep moving forward because the alternative is worse! So, we begin the year with the resolution to make things a little bit better, to prevent things from getting worse. Knowing things could be worse, and likely will be unless we create something new through our determined efforts may sound like a “pessimist’s guide to goal setting” but reminds me of one of my favorite books, Paul Watzlawick’s classic “The situation is hopeless, but not serious.” This is not pessimism, but realism, and a different kind of optimism that says that it is within our capacity to shape our future and ourselves, if only we make the choice. Wishing all a healthy and successful 2017! Stephen Stotland, Ph.D.  When is the right time to start working on better weight control? For some people the idea of starting a few days before Christmas sounds impossible, and they will instead work on a New Year’s resolution, vowing to leap into action as soon as the holidays are over. Their attitude is, “have fun now, pay later,” like those who run up big credit card bills buying gifts they can’t really afford. Now, my intention in this essay is surely not to be a Grinch. It’s important to have fun and share good times. My question is whether we can have a good time but still practice new habits? To answer this question, we need to look more closely at the concept of habit. Habits are behaviours that take place in response to specific “cues” (remember Pavlov’s dogs); they feel automatic and in some sense “driven” – that’s why the concepts of habit and addiction are overlapping and somewhat difficult to tease apart. Habits can be healthy (e.g. brushing your teeth) or unhealthy (e.g. overeating), but in all cases, have the feeling of being a part of us. To change a habit, we must pull ourselves away from what feels natural. Back to the holiday question, imagine your pattern of holiday eating in years past, and think of all the cues that trigger it. Perhaps it’s the big display of traditional foods, things you only have a chance to eat once a year. Perhaps it’s your friends and relatives offering, or even pushing, you to eat, eat, eat. Perhaps it’s the quiet time you get to spend with yourself, eating while watching too much TV. Your habits take place in a “predictable” scenario of place, people, food, mood, and motivation (the “why” of your eating). So, what’s a good goal if you decide to make a change this year? I would suggest making the smallest changes you can think of! A little less of this (e.g. sweets) and a little more of that (e.g. walks). Stay conscious of what you’re doing this year and how it’s just a little bit better than last year. Think about my “theory of behaviour change relativity,” which is, simply, that “it’s all relative,” meaning your behaviour this year relative to last year. The holiday season is an “opportunity” to get started on this process of 1. Identifying your habits, 2. Understanding the contexts in which they take place, and 3. Starting to make small changes. If you start making small changes in your habits now, just imagine where you’ll be by the NEXT holiday season. Happy holidays!! Stephen Stotland, Ph.D.  There are 7 stages of weight control which include the unmotivated stage, the concerned but disengaged stage, the contemplation stage, as well as the novice, intermediate, mastery and expert stages. In the unmotivated stage, the person does not recognize their weight problem, or thinks it is unimportant and not worth worrying about. From here one may move to a stage of being concerned but disengaged, realizing there's a problem, but not ready to think about it. As one begins to sense the importance of weight control one enters a contemplation stage, beginning to think more seriously about whether or not to attempt better weight control. During this stage, as they find more reasons to make the effort, and less reasons not to, the person gradually becomes more sure of their intention and closer and closer to implementing an action plan. As their analysis of the pros and cons shifts more to the positive and as the expectation of success increases, a decision is firmly made and the person moves from contemplation into action. Once moving into the action stage there is a long period of "apprenticeship" in which one acquires the needed skills and knowledge. In the early "novice stage", the person benefits from a clear structure and feedback. After 3 - 6 months of consistently practicing new eating and exercise behaviour the individual should have reached the "intermediate stage", with stable habits and greater flexibility. At this stage the person is quite confident about weight control and not disturbed by situational variations in behaviour. Thus, if one eats more or less "nutritious" food on some occasion, there is still a sense of moderation and therefore no fear, frustration or guilt, but instead a feeling of satisfaction and resilient confidence. Eventually, with enough practice and experience one may attain the "mastery stage," where the new habits are fully automatic and second-nature. From this stage there is still room for development, to the "expert stage." The expert can develop their own new ideas and can even teach others. Thus, the expert of weight control has both mastered his or her own weight, and can help others do the same. Many experts in weight control have overcome their own weight issue. Effective treatment can benefit from a knowledge and understanding of the stages. Different treatment strategies are appropriate for different stages. If the goal is to create "weight control experts" then treatment must go far beyond diets and exercise plans; there is need for a deeper analysis of motivation, skills, strategies and attitudes. The 7 stages of weight control provide a map of the weight control process. The higher one climbs in the stages the better the long-term prospects., but it's important to remember that one cannot become an expert without first being a novice, then intermediate and master. Stephen Stotland, Ph.D.  We must consider this question: do people really have a choice what they weigh? Can a 5' 8" 350 lbs. 45 year old man suddenly decide to lose half his bodyweight? Yes, he may make a decision, and set this goal for himself. Whether the decision is based on a realistic expectation of achieving the goal, or not, is another question. Basically, can this middle aged man, having achieved a severe degree of obesity, now achieve a normal body weight, with optimal health and functional ability? Thus, the real question is, is achieving a healthy weight within one's "self-control", or are forces beyond one's control simply too powerful? To answer this question I will make use of an analogy. The need to breathe is obvious to all, as within a few seconds of being deprived of air one begins to show ill effects. No one would suggest that not breathing is a choice. But even a function as automatic as breathing can be controlled at times and perhaps permanently altered through persistent efforts. We can slow our breathing, practice deep breathing, and engage in increased (aerobic) breathing (e.g. while running, climbing, lifting, swimming). We can also choose what we breathe (e.g. cigarette smoke, polluted air, fresh air). All of these "intentional" manipulations of breathing may have significant long-term effects. Similarly, eating is not a choice (we need to eat) even if the consequences of not eating come more slowly than those of not breathing. But clearly, if we have some control over breathing, then we certainly have some control over eating. It is within our power to choose when, where, what and how to eat. "Weight regulation" refers to the various processes determining one's actual bodyweight. Genetic factors affect metabolism, energy levels, athletic ability and enjoyment, food preferences and eating styles. Environment too is a strong influence on eating and activity behaviours. It is within those important contexts - one's genes and environment - that one engages in the "self-regulation" of weight. One chooses to be thinner, healthier, fitter, and then uses strategies to achieve the goal, but the outcome of such practices are influenced by genetics and environment. Here is where the capacity for self-awareness is important. An individual like our middle-aged gentleman can become more conscious of his body, mind and environment, and start using this self-awareness to guide a process of change and self-improvement. Small choices made consistently can gradually modify his physiology, mental programming and social situations, creating new habits and a new lifestyle. It truly does start with a choice, deciding to make the change. He may not become a model or an Olympian, but he will surely be healthier and feel better about himself. Stephen Stotland, Ph.D.  Eating disorders are self-destructive habits that take on greater and greater centrality and importance in the mind and life of the sufferer. As one progresses into a more active and severe eating disorder, one becomes more "restrictive" and/or "impulsive" in eating and exercise behaviour, and the more one's general emotional state is negatively affected. The weight control attitude associated with an active eating disorder is characterized by varying degrees of restrained (restricted) eating and disinhibition/binging, and more or less extreme weight loss goals. Different combinations of anorexic and bulimic behaviour patterns are possible. As people recover from eating disorders they become more flexible and moderate in their eating intentions and behaviour. The recovered patient remains more concerned about her weight and more restrained in her eating compared to the non-eating disordered population, but there is a significant increase in the level of moderation and in the integration of this behaviour change. The changes in weight and eating attitudes with recovery are correlated with equally significant changes in mood, life satisfaction, coping and body esteem. The amazing thing about someone with an eating disorder is that she pursues a course of action which she knows has negative consequences, and yet sticks to the disorder, much like an addict. That's why you can't treat eating disorders by prescribing diets, or even by hospitalization, without dealing with the essential irony of the problem. You help someone gain self-awareness and deal with emotional coping, and she finds her own motivation to change. As Bruch and later Garner and Garfinkle pointed out, there is an overriding importance in the overall cause and maintenance of the disorder of a feeling of ineffectiveness, even defectiveness, and a desperate attempt to organize oneself in the service of a goal, even if that goal has negative side effects. Unless a person can overcome the general negative feelings about herself, she will not be capable of motivating herself to recover from the eating disorder. The goal of recovery must become stronger than the attraction to the habit. As the motivation for recovery grows and the change process proceeds, the restrictiveness and impulsiveness of eating thoughts and behaviours are normalized. Finally, it's important to remember the recovery from eating disorders is a long-term process. Recovery should be measured over several years. Stephen Stotland, Ph.D.  Why would you want to give up food for a liquid meal replacement? There are actually several reasons why this might be a good idea. In some cases Optifast is used for the purposes of very short term weight loss, for example by patients preparing for a surgery in which losing weight may actually reduce the risk and speed recovery (e.g. weight loss surgery, other gastrointestinal surgeries). This effective weight loss method might also be used by women who want to increase their chances of becoming pregnant in the context of fertility treatment. The most common use of Optifast is as part of a long-term medically-supervised weight management program. In this case, the use of a meal replacement is step one of a multi-phase approach. In the present discussion I will examine the role of Optifast in the program that we offer in our clinic. First, a quick description of the product. Optifast is a meal replacement that can be used as a total substitute for food, providing all of the basic nutrition that one needs in a very low calorie package. The Canadian version provides 900 calories per day. That does not sound like a lot (it isn't), but the formula includes adequate amounts of protein, fat and carbohydrate for the average person -- medical supervision is necessary, because there are some cases in which this isn't true. In our program, Optifast is offered as a "choice," one of several treatment options. The main reasons that an individual chooses this route is its simplicity and efficacy. In other words, taking 4 liquid meals ("shakes") at 4 hour intervals during the day is pretty straightforward and, given the small amount of calories consumed, the resulting weight loss can be quite dramatic. So patients select this approach because they are highly motivated to get off to a fast start with a safe and structured solution. Of course, giving up eating comes with certain costs. This is a practical method, not a gourmet one. The taste of liquid meal replacements is not surprisingly quite bland. Most people adapt fairly quickly, finding ways of preparing it to their own taste, and some people even come to like it. There are social inconveniences as well, such as not being able to join in a meal with others, or having to cook but not eat what one has prepared. Physically, there is an adaptation period, several days in which one may feel tired and hungry. These costs are short-term, however, and easily handled by most people. Some people are skeptical about the long-term effects of using meal replacements, and for good reason. One is not about to stay on such a product forever, so what happens when one stops? In many cases, people who use such products, lose substantial amounts of weight and then go back to food, quickly regain their weight. They end up feeling disappointed and discouraged and question the value of the product. The key point is as follows: meal replacements on their own have absolutely no long-term usefulness. Most people need professional support to guide them back to food, and towards the long-term behaviour changes needed to ensure weight loss maintenance. So why not skip the "artificial" products and go straight to working on the behaviour changes? That certainly works for some people, but for others the intial simple, structured and effective meal replacement phase is a great way to get started. In a well-designed treatment program, the transition back to food will be slow, and will allow the patient to find a way of eating (and exercising!) that fits their preferences and lifestyle. This is a complex question that should be discussed with the health professionals supporting you in your weight loss efforts. There is no one-size-fits-all approach, so you must find the one which is right for you. Stephen Stotland, Ph.D.  Let's try to define what we mean by weight control "practice." Firstly, like any practice, it begins with a desire to improve something, an intention to change, a goal. In other words, we begin by considering the quality of motivation. Progress comes from turning motivation into action....keeping up a consistent practice. The more effort that's put into improving eating and exercise, the better the weight control outcome. That's true on both a short- and long-term basis. In our view regular practice leads to "internalized" change, meaning that the new habits become automatic, natural and desirable, and this leads to better long-term weight loss results. So practice, practice, practice !!! Stephen Stotland, Ph.D.  Is there a 'right diet' for everyone? How much depends on the individual? How much is universal? Yes. And no. The simplest question is "energy," or how many calories one needs. Individual energy expenditure is only partially predictable with universal formulas. There are large individual differences in actual energy expenditure. Beyond calories, there are other questions about optimal nutritional intake - how much protein, fat, carbohydrate, vitamins and other micronutrients do we need? The optimal diet seems to be low in fat, moderate in protein, and high in "good" carbohydrate and fiber. The right diet for an individual depends on their physical condition and activity pattern. With increased activity comes additional nutritional needs (more energy!). Achieving the right diet is an individual process, based on our history, habits and preferences. In our clinic we help promote a self-discovery process that does not depend on a particular diet or overly rigid control of eating and exercise, but a natural way of being that is consistent with one's values and preferences. The real purpose of obesity treatment is to support the individual in discovering a lifestyle that works for them. That is the "right diet." Stephen Stotland, Ph.D.  A person wakes up one day and realizes that s/he is in bad shape, already showing signs of poor fitness and at risk for serious diseases and reduced longevity. It may be her/his doctor who has made this reality extremely clear, or it may be other events and experiences that lead someone to this realization about their current health and fitness levels. When this "awakening" happens, and not before, then a door is opened to the potential for greater wellness. Once one has grasped the seriousness of the current state and glimpsed the possibility of improving it, then the motivation to change will be there. On the other hand, a person who feels pessimistic about weight control is not likely to start, let alone succeed in the long-run. Where does the self-belief needed to drive and maintain long-term effort come from? Firstly, confidence is developed through practice - practice makes perfect they say, and practice builds confidence. A second source of inspiration is the imagination. Can the person see herself in a "transformed" state, with large and dramatic improvements in the quality and quantity of eating and exercise, health and fitness? Up to what point does it all seem feasible? Desirable? Acceptable? Sometimes there is a lack of self-belief and the ability to even imagine achieving one's goals. What is stopping the person from visualizing this change? The obstacle in this case is in their own head. It is this level of thinking - the core beliefs and mental blocks - that must be explored and worked on in order to allow successful obesity treatment. Stephen Stotland, Ph.D.  We all must learn to "carry our own weight" they say, which means to take responsibility for ourselves and not to expect others to "carry us". Some people have more to carry, as they have had the misfortune to come from difficult family circumstances, unhelpful environments and little opportunity for education or personal growth. And yet some who began in the most disadvantaged of situations have emerged, found ways to thrive and find happiness -- we say that such individuals have "resilience." These individuals have discovered how to unburden themselves of unnecessary weight, to keep only what is essential and valuable. Why do so many of us appear "weighed down" by our emotions and problems, as if we are carrying the "weight of the world" on our shoulders? Why not just set down the heavy load, and allow ourselves to feel light and free? This is not merely a rhetorical question, but a central philosophical and psychological problem. Each of us must look deeply into our own eyes, into our soul, to our past, present and imagined future, to make sense of existence, to see ourself clearly, to finally say, "I understand why I do this," before we will be able to let go... To understand ourselves we look within, but we can also learn by looking at the outside, seeing ourselves as another would, as an observer. In this sense, look at your physicality, at your body, your posture, your facial expression, your movements. Look at how you do things, your attitude. To take a simple but relevant example, look at how you eat. What is your attitude towards the food? Do you value the food? Respect it? Give it the proper attention? Use it sparingly, rather than greedily? Do you consume it slowly with mindful pleasure, or aggressively and quickly? Look at your attitude towards food and the act of eating as a reflection of your attitude towards yourself, other people and life itself. Perhaps this is a radical idea, but give it a chance... When we carry too heavy an emotional burden it is bound to come out in many small but ultimately significant ways - in our eating, sleeping, moving, breathing. The central human dilemma is to gain self-awareness and to find philosophical meaning in our lives. This is not merely an intellectual, academic exercise, but the key to health and happiness! Stephen Stotland, Ph.D.  Weight problems are created one bite at a time. That extra few mouthfuls, the second or third helping, the mindless nibbling... What is it that motivates these behaviours? Is it hunger, restlessness, anxiety, or pleasure seeking? If you ask people why they overeat, the usual answer is "hunger," but when this takes place only an hour after a meal it can't be "real" hunger. It can be more accurately described as an "impulse," which means simply an urge to act in a certain way. The basis for the impulse is habit, which is a learned reaction to a specific set of conditions. For example, one may get the urge to eat as soon as she/he sits down to watch television in the evening. The sequence of events is: turn on the tv....think of eating....feel an "urge" to eat...go eat! Pretty simple, and not much thought involved. Sometimes a battle ensues, as the person simultaneously has anticipatory guilt feelings ("I shouldn't"). A test of self-control, with the outcome depending on the momentary physical and emotional state of the person and the strength of the habit. The essential nature of impulsive overeating is what is often called "mindlessness." The sequence of thought, feeling and action is so quick and automatic that there seems little opportunity for conscious self-control. Examine your thoughts and feelings the next time you're about to cross the line into eating excess. Ask yourself what it is you really want. Is it really more food? What do you think will happen if you don't eat? How does your body feel? Can you relax and let go...wait for the urge to pass? Is it worth the effort? Are you worth the effort? Bringing awareness to automatic reactions is step 1. Choosing an alernative course of action is step 2. It takes effort, repetition and consistency to change habits. You have to really want it, but it can be done... Stephen Stotland, Ph.D. |

This blog presents some of our ideas about the key issues involved in achieving successful long-term weight control. Archives

December 2022

|