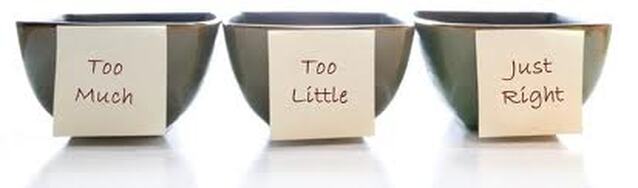

It’s obvious that you don’t have to be “hungry” to eat. We eat for all sorts of reasons, such as the time of day, the availability of food, seeing other people eating, as a distraction, reward, coping mechanism, or “just because” we feel like it. Let’s define hunger as a state in which we experience physical sensations resulting from a lack of food energy. We may or may not initially pay attention to those sensations, or label them as signs of hunger. As the sensations intensify, we are likely to become increasingly conscious of the empty feeling and rumblings in the stomach, perhaps a feeling of fatigue, and a growing need to eat. Eventually, we may become irritable and have a hard time concentrating on work or other matters. We might think of a Hunger Scale with ‘extreme hunger’ on one end and its opposite – ‘extreme fullness’ – on the other end. Let’s define extreme hunger as 0 and extreme fullness as 10. Those states are easy to imagine, but what about all the steps in between? What does a 2 feel like? Or a 4? Where does fullness begin? At what point does fullness shift into overeating? Is the middle ground between hunger and fullness a “neutral” state? When you say you are “hungry” an hour after supper, what sensations are you actually experiencing? Thinking about the hunger – fullness continuum we realize that these are complex concepts. Neither hunger nor fullness are straightforward, or easy to define. They are partly physical and partly psychological, depending on attention, interpretation, and situation. The implication is that there is only a loose association between these internal states and our eating behaviour. Sometimes we eat because we’re hungry and stop because we’re full, but not always. The psychologists Peter Herman and Janet Polivy discussed this some time ago in what they called their “Boundary Model” of eating. In their model, individuals have well-defined hunger and fullness boundaries, which are the points on the continuum beyond which the person feels strong physical feedback indicating hunger or fullness. This feedback is in some sense painful or unpleasant, and it motivates us to eat, or stop eating. What is interesting is that each person’s boundaries may differ, so that given an equivalent physical state (degree of energy depletion) one person would describe it as a 4 (little or no hunger) and another as a 2 (strong hunger). The same is true, they suggested, for the fullness boundary, so that the same amount of food may produce a 6 (little or no satiety) for one person and an 8 (very full) for another. These differences may be due to learned perceptions, or inborn sensitivities. An open question is what is the effect of eating less, does it eventually cause our stomach to “shrink?” The stomach is a small organ (about the size of a fist) but can stretch to accommodate large amounts of food. In fact, the stomach is always stretching and shrinking as we eat and digest food, allowing the stomach to empty, but it is true that if we stop overeating the stomach is, by definition, less often in a highly stretched state. More importantly, if we start eating less we may eventually adapt to the sensations produced by the smaller meal and come to define that as fullness. It is not so much that the stomach has shrunk, but our expectations that have been retrained. That is the kind of learning that we hope for, and that will make healthy eating choices “easy,” and not forever a matter of restraining oneself. What about the part of the continuum between strong hunger and fullness, say the 4, 5 and 6 on the scale. Herman and Polivy called this the physiological “zone of indifference” (ZOD) meaning that the body’s homeostatic systems, those responsible for motivating us to eat or stop eating, are indifferent to whether we eat or not when in this neutral zone. We receive no strong feedback signals, and so we are “free” to choose to eat “if we feel like it.” Thus, in the ZOD, we are especially prone to eating in response to emotional, social, and food cues. It is interesting that people usually say that they eat because they feel hungry, in effect mis-labeling the real reasons, because we have been taught that the only good reason to eat is because we are hungry. A good step is to be honest with oneself about one’s motives and admit that one eats for other reasons than hunger. Several writers and clinicians tell people that the way to eat better and be healthy is to listen to signals of hunger and fullness and base their decisions on trying to satisfy their physical needs. While this is a nice idea, there is no evidence that it works as a method of weight control. As we have discussed, hunger and fullness are complex and confusing signals. In our view, using hunger and fullness signals to guide eating decisions is an “advanced” strategy, one that we introduce to our patients months into the treatment process. For the vast majority of obese individuals, preliminary work based on creating reasonable eating routines and structures is necessary to get the process started. Once the individual has learned to do that, and has gained confidence and flexibility in weight management, we can begin to shift to a more internal awareness-based type of self-control. If you’ve read our earlier blog post on the stages of weight control, you know that this shift from external to internal control strategies takes place in stages 5 and 6. It’s important to keep reminding ourselves that you need to walk before you can run, and to run one kilometer before attempting a 10K – in other words, you need to be a novice, before you become an intermediate, or a master. Keep working at it! Stephen Stotland, Ph.D. Comments are closed.

|

This blog presents some of our ideas about the key issues involved in achieving successful long-term weight control. Archives

December 2022

|